Instruments of War

A dozen Coast Guard sailors arrived at their new station in Alameda,

California, prepared to take up weapons of choice—musical

instruments—

against the Japanese. The Manhattan Beach Training Station musicians

would soon board a ship destined for ports in the Pacific. Their new

role in

the war began with chaos and uncertainty on arrival at the Naval Air

Base in Alameda in early March 1945.

There was little to do at first other than muster twice a day, play

cards, wait, wonder, worry. The band members hoped they would, in

some capacity, function as a band, but they had no band leader.

Surely, they were not assigned to the portal of the Pacific War to

just play music. They passed the time and tried to thwart

uncertainty with dinners in Oakland, second-rate movies,

sightseeing, and card games. Several musicians spent a comfortable

night as guests of the San Francisco band, one of ten regional Coast

Guard bands formed during the war. Their gratitude to the San

Francisco band was tempered by a nagging question: Why was the San

Francisco band continuing its musical war role while the Manhattan

Beach band was gutted and its leading musicians, shipped out? Was it

the image of the white dress uniforms and polished shoes they wore

as they marched and played in Manhattan streets while bloodied

soldiers fought in grim conditions? Was it a sense of privilege they

assumed and at times flaunted as they horsed around far from combat

zones? Was it triggered by an inappropriate incident involving a

drumstick that occurred while the band was being reviewed by an

admiral a week or so before they were ordered to California? While

band members speculated and differed over the causes of their

transfer, they ignored the Coast Guard’s preeminent reason—the war.

They left wives behind in New York with barely a goodbye. The wives

quickly bonded as a support group to endure the absence and anxiety

over their husbands’ new role in the war. The musician-sailors

bonded over the confusion and anxiety of their new assignment.

The Alameda Naval Air Station was created just in time for World War

II and expanded throughout the war to accommodate air units, carrier

groups, supplies, Naval personnel, and this new crew of Coast Guard

musicians.

The Manhattan Beach band musicians settled into the barracks while

they awaited word of their new roles as the war dragged on. They

learned they would serve on the U.S.S. General A.W. Greely,

a new ship of which they knew little and even less about its

destinations. What would band members do on the Greely, play

music, fire guns, man landing vessels, attack Japanese ships? Rumors

flourished amid news of the Coast Guard’s and Navy’s roles in the

Battle of Iwo Jima, in progress as the musicians arrived in San

Francisco. Some 7,000 Marines died taking the island. Was that a

foreshadowing of their mission? Were they to play a role in taking

Okinawa, the next teppingstone en route to the Japanese mainland? If

the Greely were to serve as an attack transport—a rumor

prompted by the 5-inch guns fore and aft—she could be a high-profile

target for artillery on Japanese shores. As reliable information

seeped in, band members learned the Greely was not an attack

transport. She was a troop transport, a ship that delivered troops

to staging areas, not beachheads. The musicians’ relief was brief.

Where were the staging areas? Rumors flew furiously. Some said the

destination was India, which involved sailing through hostile waters

of the Pacific and Indian oceans. Others said Australia, a

relatively safe location if the ship could evade torpedoes along the

way. Musician Art Schnell, an optimist at this point, believed they

were headed for Hawaii. Or maybe, if Germany surrendered, the Greely

would sail the Atlantic, bringing troops home from Europe and

docking in New York Harbor not far from wives of the Greely

musicians. In a flurry of letters between San Francisco and New

York, wives and musician-sailors exchanged hopes and fears while

they sought reliable information amid the uncertainty of war.

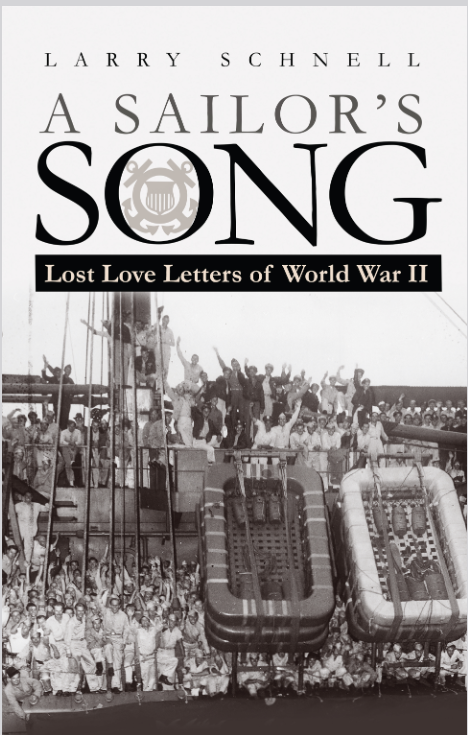

Finally, a band leader showed up and called a rehearsal, relieving

musicians of idle time to churn the unknown into anxiety. Harold

Brody had to get the band in shape quickly as the musicians would

perform for the Greely commissioning, a formal event

attended by officers of the Navy, Army, Coast Guard, and Marines as

well as political dignitaries. The band sounded ragged during the

first rehearsal, but the Manhattan Beach musicians were among the

best and would get it together for the big event. After that, they

would play for crew loading the ship. As they helped prepare the Greely

for its maiden voyage, they observed and shared bits of good

news—musical

instruments were among the cargo.

Band members did not know how they came to be known as the Greely

Grenadiers, but after it was mentioned at a performance and

published in the ship’s newsletter, it was official. Although some

musicians did not like the name, they liked the implication that the

band would play while the ship was at sea, that music had a role in

war. They would soon learn that soldiers awaiting deployment could

enjoy calming or inspirational music. That same music could sooth

the minds of soldiers returning from years of battle.

By the end of the Greely’s voyages, after

destination rumors had been replaced by travelogue, after fresh

troops had been delivered and war-weary

troops returned to their families, the Greely would earn a

reputation for distinguished voyages and service to veterans.

By the war’s end, the Greely had completed a

circumnavigation via India, three additional trips to India and

other Pacific destinations, and two transatlantic crossings. A Greely

newsletter proclaimed the ship’s first trip to Pacific destinations

the longest maiden voyage for a warship—almost 13,000 miles—and the

longest voyage for a troop transport. Many of more than 10,000

passengers on return voyages were among the longest serving troops

in the war. Returning from France, she repatriated the 2nd Infantry

3rd Division (Red Diamond) after its troops helped drive the Nazi

armies out of France and back to Germany. Returning from her second

Pacific voyage, the Greely brought home Merrill’s Marauders

after two years in the jungles of Burma, the Flying Tigers, after

almost four years in China, the U.S. Army engineers who built the

Ledo Road through Burma, the Kachin Rangers who fought the Japanese

with help from indigenous people, and other service groups. These

famed fighters debarked the Greely in New York to the cheers

of thousands and to the music of the Greely Grenadiers, the

band that earned her recognition as the only military ship to have

its

own band aboard from the day of commissioning.

The Greely also delivered mail—ship to shore and shore to

ship, thousands of pounds on each voyage. Letters were the only

means for sailors and soldiers to keep in touch with loved ones. The

Manhattan Beach musicians joined millions of Americans writing

letters that were packed in mail sacks and transported throughout

the world in the holds of ships like the Greely. Couples

struggling to maintain a marriage in the uncertainty of war relied

on letters to share their hopes for the future, for themselves, and

for a nation. Letters from troops in war zones encouraged optimism

for loved ones as they portrayed a lifestyle as remote from the

reality they left behind as the distance separating them. Those in

combat found comfort, encouragement, and hope in letters shipped to

distant military bases and battlefields with the hope that the

receiver would be alive to read them.

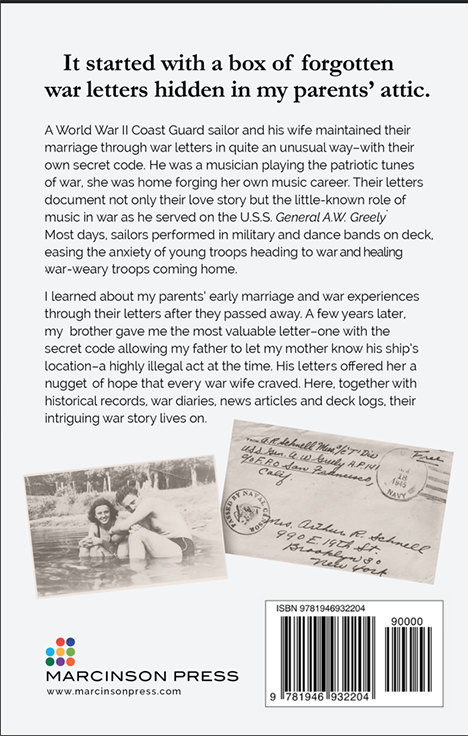

Kimberly Guise, senior curator at The National WWII Museum in New

Orleans, studied thousands of letters to and from troops separated

from families by World War II. Letters are primary sources that tell

enduring stories of the personal side of the war. “These singular

resources will survive far beyond the time when the last WWII

veteran has passed,” she wrote. “The information they provide is

immediate, requiring no instruction about how to interpret them.

They speak for themselves. Each piece tells us something new, adding

a unique personal vision to the immense story of World War II.”

The exchange of letters between Arthur R. Schnell, Musician 3rd

Class, and wife, Florence, reveals much more than the personal

aspects of war.

The couple was committed to a life of music, and the information

they exchanged reflects the importance of music in the military and

on the home front. Flo’s letters describe a woman taking charge of a

range of issues from disentangling her 1933 Plymouth coupe from a

fender-bender to managing a musical career in the absence of her

husband. Art’s letters provide an intriguing inside look at the role

of music in war, on a military base, and on a ship. His letters

describe the personalities, talents, and temperaments of the

musicians who turned passion into patriotism. Together with

historical records, the Greely War Diaries and Deck Logs,

newsletters, and news articles, these letters portray the importance

of music in supporting the war, troops, and home-front families.

While millions of war letters between loved ones were written,

mailed, and shipped, Arthur Schnell received the first letter from

his wife on March 14, 1945, more than a week after arriving in San

Francisco. “This afternoon I received the first letter that anyone

in the band has received since coming out here, and was I proud,

which just proves that my darling is the best ‘Mousie’ (the couple’s

term of endearment),” he replied.

In early April, musicians were ordered to pack their bags, as they

were leaving in twenty minutes for Treasure Island to train and

prepare for an accelerated shakedown cruise. Letters would be

censored, Art warned. “Naturally while we are on board, our mail

will be censored so remember the code,” he wrote in a letter mailed

from a Post Office in San Francisco beyond the eyes of censors. When

I first read the letters, I had no idea what code my father was

referring to. |

|

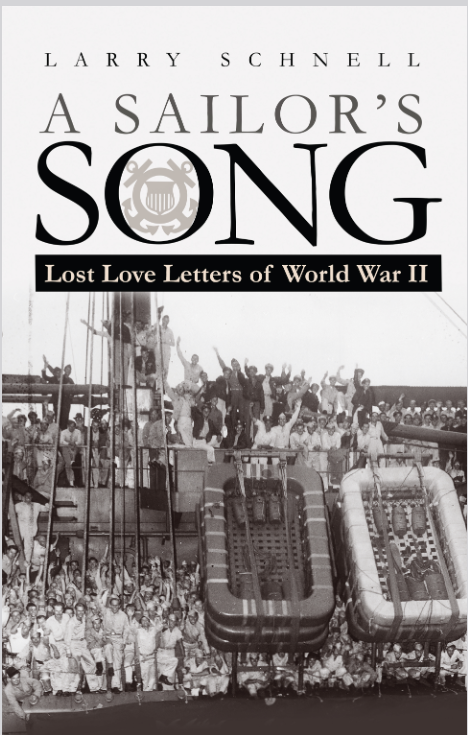

A Sailor's Song on the air

IPM News public radio Champaign-Urbana explores the themes of

music, war letters, love in an interview with Larry Schnell,

author of A Sailor’s Song: Lost Love Letters of World War II,

April 4, 2025.

217 Today: How a

hidden box of love letters became a historical memoir of WWII,

with Anna Koh.“In today’s deep dive, we’ll learn about a new

memoir from local author Larry Schnell that explores the

little-known role of music in war.”

https://ipmnewsroom.org/217-today-how-a-hidden-box-of-love-letters-became-a-historical-

memoir-of-wwii/

When The Moon Sings

WRUU Savannah with host P.T. Bridgeport explores the importance of

music and letters in World War II with Larry Schnell, author of A

Sailor’s Song: Lost Love Letters of World War II, April 19, 2025.

Mr. Bridgeport, whose father served in World War II and was a

prisoner of war, provided an excellent forum for discussion of the

recently published book, focusing on both military and home-front

morale.

“You are providing people with a sense of what it was like to be

in the war both from the military perspective and the civilian

perspective.” https://www.wruu.org/broadcasts/57603/

A Sailor’s Song: Lost Love

Letters of World War II is a welcome look at the 40s,

America in the world war,

one family’s separation and survival, and the Coast Guard. It is a

nostalgic

and poignant look that makes me proud to be an American. It was a

time when our

people put aside their political, social and economic issues, and

fought

together to lead the world to triumph over fascism. Based on his

father’s

correspondence with his mother while he served in the Coast Guard,

Schnell’s

readers are fortunate to have this story of life at sea and the

home front

during the war. A Sailor’s Song is solid cultural history

and, more

important, a very readable story that anyone interested in the

Greatest

Generation will enjoy.

Dr. Robert L. Gold, Ph.D.

Historian, professor, author

This is a lovely gem of a story about band

music and love

letters exchanged in wartime between the author’s parents

Arthur and Florence Schnell.

Art, a music teacher and trombonist, enlisted to serve in the

Manhattan Beach Coast

Guard Band during WWII. He

and an elite group

of his fellow musicians travel to California for deployment on

the USS A.W.

Greely, a newly built personnel transport ship which

served the China, Burma

and India theatre of operations. Their

primary

role was to provide entertainment to troops and support staff

on route

to war arenas, and comfort to those headed home after enduring

deprivation,

injury and trauma. The author blends the love story between

his parents,

separated by Art’s wartime deployment, with the rigors of

working on a naval transport

ship that, from 1945-1946, sailed through the Pacific, Indian

and Atlantic

Oceans, and circumnavigated the world to transport troops,

supplies and mail.

We are amused to read Art’s carefully coded

letters, in

which he secretly revealed his geographic locations to his

wife, to evade the

watchful eyes of the censors. Author Schnell explains the

complexities of delivering

mail to service members throughout the world. We also learn

how Florence,

affectionately called Flo, dealt with the absence of her

husband, while sharing

an apartment with another deployed musician’s wife. Flo was a

working musician

and teacher, and she gained an additional sense of

independence and strength during

Art’s absence, yet she devotedly maintains a steady

correspondence with him.

A blend of narrative nonfiction and

historical memoir,

A Sailor’s Song provides the reader with detailed

information of the

role of musicians in the US Coast Guard. It

is a glimpse into the love story of two people

separated by war yet determined to keep their romance alive.

Susan Waller Lehmann, Author, Private

Investigator, Journalist

|